Stairway Troll

Originally written February 25, 2015

I am currently taking up residence on the stairway landing between the third and fourth floors of our guest house, where the wifi has been most reliably good today. It’s a nice way to meet all the PIH staffers I don’t know yet, as they pass me on the way to their rooms and laugh knowingly at the lengths it sometimes takes to get a good signal. One of the long-term staffers jokingly calls us “stairway trolls.”

It’s late and I’m still a bit jet-lagged so I know I should go to sleep, but I am bursting at the seams with new information and experiences and I’m afraid that if I don’t write it all down, little details will start slipping away. The past two days of training have been fascinating.

Blogging in the stairway. I go where the wifi is!

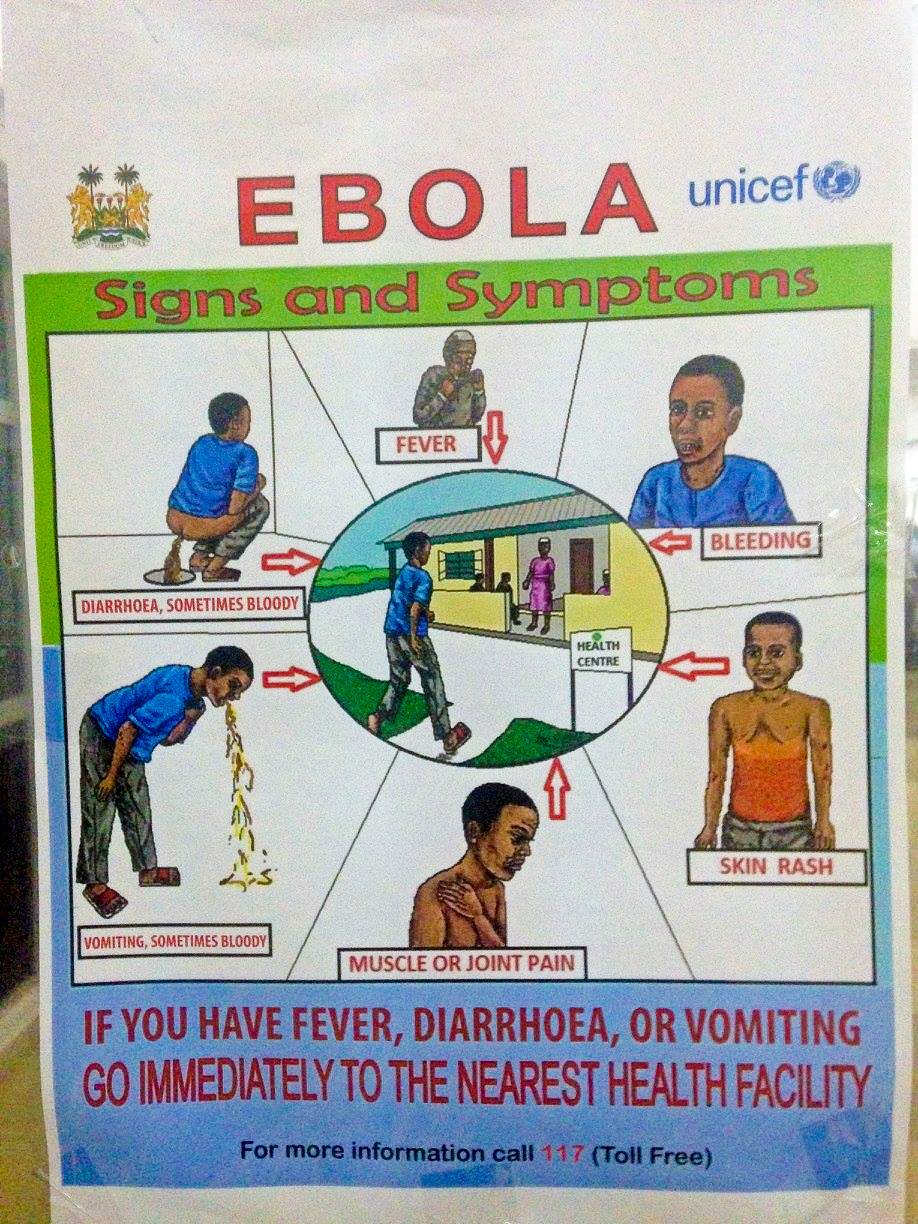

We spent most of Tuesday learning the case definition of Ebola, which sounds boring but turns out to be the bedrock of everything we do here. Patients will show up to triage at an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) with a variety of symptoms, and it’s our job to decide who should be admitted to be treated for Ebola, and who should be sent to another healthcare facility or home. Sounds easy, right? From what the news tells us, it seems like turning up at an ETU with a fever would be an automatic admission.

The trouble is that there are several tropical diseases here that have similar symptoms to Ebola (Lassa Fever, for example, looks very much the same with the exception that Ebola patients commonly have hiccups).

So why not just admit them to be safe, and then figure out what they have for sure once you have them quarantined in the ETU? Because of the nightmare scenario of admitting a person who turns out to only have malaria, but then they catch Ebola from having some contact with another patient while they waited to be diagnosed.

Patients who are admitted to an ETU through triage join the other non-confirmed patients in the “suspect” ward. This means they automatically live in the Red Zone, the high-risk area that we healthcare workers can’t set foot in without being completely suited up. As much as we will try to keep suspected Ebola patients separated from each other before they are confirmed, it’s not possible to guarantee that one won’t infect another.

One of our case studies described a patient in the suspect ward (who turned out to be Ebola positive) who was delirious, ripped out his IV, and wandered into other suspect patients’ rooms, spreading his blood everywhere. If any of those other patients had turned out to be negative, now they were at serious risk. Essentially, it would be horrible if patients came to the ETU Ebola-negative, and then caught it there.

We don’t want to admit non-Ebola patients to the suspect ward if at all possible, but we also don’t want to send someone home who turns out to have Ebola after all. Here’s another nightmare: You triage a patient and wrongly decide that her symptoms don’t meet the case definition for Ebola, and she goes home and infects her entire family.

If Ebola tests were instantaneous and 100% accurate, we wouldn’t face scanarios like this. Unfortunately, they aren’t.

The amount of time it takes to get results on a PCR (the blood test for Ebola) has decreased during this outbreak in many cases from days to hours, but most places don’t have a lab that is sophisticated enough to handle blood samples as hazardous as these. And even if your patient’s Ebola test comes back negative, they don’t get an automatic ticket home. In the first few days of the illness the viral load may not be high enough to be detected by the test, so they’ll have to remain in the ETU for a few more days and re-test, to make certain that the initial PCR wasn’t a false negative.

One of the Sierra Leonean nurses told me today that she felt their most egregious mistake at the start of the epidemic was that they sent patients home after one initial negative test. She was clearly upset as she recalled that they had sent home one of their health workers despite his symptoms because his Ebola test was negative, only to have him return a few days later and die shortly thereafter.

Now I’ll complicate things even more. It would be easier to adhere to the case definitions that guide us to admit a patient if we were certain that every patient was being perfectly honest. But people who don’t want to be admitted to an ETU often hide their symptoms, denying that they’ve had diarrhea or vomiting and insisting that they feel fine. You may also triage someone who has no fever, which lowers your suspicion, until you ask the right question and find out they’ve been taking Tylenol in order to bring their fever down. So sometimes I have to be a detective as well as a nurse.

Many of the examples I’m using have come from real case studies that we discussed in small groups in class, which for me has been the most valuable part of training so far. You think you’re somewhat prepared, until you find your group split down the middle trying to decide what to do with the case you’re discussing, which is an actual situation that clinicians faced in an ETU.

We were faced with another sobering reality today, as Ebola survivors had been invited to our training to share their experiences with us. They sat in a row at the front of the class, bravely recounting the hell they had somehow managed to survive. While one survivor took his turn to speak, others stared blankly at the floor as if re-living their experiences. Another leaned back and covered his face with his hands, seemingly willing himself not to remember what he’d seen.

Most of the survivors we heard from contracted Ebola while caring for their ill family members early in the outbreak. In one case, a patient was sick in a government hospital but the nurses refused to care for her because they feared Ebola. When her family came to the hospital to do what the nurses wouldn’t, they all became infected.

In another case, an ill woman refused to go to the hospital, so her family members who were health workers cared for her at home. They started IVs on her with their bare hands, and of course infected themselves.

One man told us that when he went to an ETU his family had no hope for his survival, and that “with every tick of the clock, they called me to ask, ‘Are you ok?’” Their experiences in holding centers (which screen patients for Ebola and transfer them to ETUs if necessary) were horrific. One man recalled sharing a toilet with 10-15 people, diarrhea and vomit covering the floor, leaving anyone who didn’t already have Ebola to almost certainly be infected. The medics were so terrified of their patients that they handed them medicine through a barbed wire fence.

“Nobody helps anybody,” he said. “It’s like the day of judgment.”

Once they were transferred to an official ETU, many described how grateful they were for the competent care they began to receive. One survivor explained that healthcare workers in the ETU were confident in their PPE, and therefore not afraid to enter the ward and care for their patients. They repeatedly thanked their Sierra Leonean caregivers, insisting that “the staff are making so many sacrifices.”

When they were asked what the worst and best moments of their experience had been, I was certain the survivors would all say that their best day was when they were pronounced Ebola negative and discharged. But most of them described that moment as conflicted; although were overjoyed to have survived, they knew they had to return to lives in which many of their family members, including spouses and children, had died. One man’s wife died of Ebola on the same day that he was discharged home, cured.

Surprisingly to me, most of the survivors described their “best” moment as an experience with a healthcare worker. It put faces to the constant message we are hearing that providing quality, humane care in the ETUs is essential. At the beginning of the outbreak, the care in ETUs was horrible and degrading (how many photos did you see in the news of patients dying alone on a cement floor?). Many people chose to keep quiet if they were sick, terrified of what would happen to them if they turned themselves in. Our trainer told us of one case in which a patient’s mother was told that he had died in an ETU, only to have him return to his village cured a week later. His neighbors ran from him, believing he was a ghost. After thinking that her son had gone to an ETU and died, the mother refused to seek treatment when she fell ill, and she died of Ebola at home few days after her son returned.

Part of Sierra Leone’s public health campaign to encourage people to seek treatment

Although ETU care has greatly improved (and it is now illegal to remain at home if you have Ebola), some people still resist seeking treatment. Confirmed Ebola patients are interviewed to determine who they have been in contact with since showing symptoms, and those contacts are actively monitored for 21 days. Community health workers visit them at their homes to check their temperatures and ask about symptoms, but it can be difficult to get the true story.

Our trainer encouraged asking the families to step outside of their houses to take their temperatures, using the example of an old woman who told the health workers she felt fine, but was unable to stand up when they asked. In other cases, people who are aware of what time the health workers are coming have removed their sick family members from the home to hide them. There has been a big push to involve local leaders in the process of monitoring; as our trainers pointed out, the villagers will never trust us as much as they trust an authority figure they already have faith in.

There is also an intense focus here on safe burial practices. Since an Ebola patient’s viral load increases the longer they are sick, corpses are extremely infectious. Studies have shown that the virus can live on dead bodies for 6 days.

In a culture where washing the body of the deceased is a common and important ritual, these practices spell disaster. We were told that some burial rites include mourners washing their faces with the water that was used to clean the body, or in extreme cases even drinking it. While that may seem abhorrent to us, try to imagine if a stranger from another country wanted to take the body of your child from you without a funeral or a coffin. It’s easy to understand why many Sierra Leoneans refuse. Unfortunately, this means that a single funeral can set off a chain reaction in which everyone who attended contracts the virus.

Sierra Leone’s campaign to change its citizens’ burial practices during the outbreak

I could go on and on, but I should follow the health workers’ cardinal rule (to take care of myself first) and go to bed! It has been a fascinating few days. I take notes furiously and hope that it’s all sticking in my brain somewhere, ready to be called forth when I need it in the coming weeks. I’m excited to get into the mock ETU tomorrow and start practicing getting my hands dirty (or rather, my outer layer of gloves. Never, never my hands).

Next post: Trained and Ready

Previous post: National Ebola Training Academy Begins

You Might Also Like:

This post contains affiliate links. This means that if you decide to make a purchase through any of the links we recommend, we get a small commission at absolutely no cost to you. This helps with the cost of keeping this site running – so thank you in advance for clicking through! And not to worry, we don’t recommend anything we don’t fully believe in or that doesn’t align with our values.